Contents

Christopher Alexander (who wrote A Pattern Language) on what it means for the built environment to be alive, which is necessary for us to feel alive within it:

A building or a town becomes alive when every pattern in it is alive: when it allows each person in it, and each plant and animal, and every stream, and bridge, and wall and roof, and every human group and every road, to become alive in its own terms.

And as that happens, the whole town reaches the state that individual people sometimes reach at their best and happiest moments, when they are most free. (Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building)

Erin Kissane writes about three qualities of living vs. dead spaces:

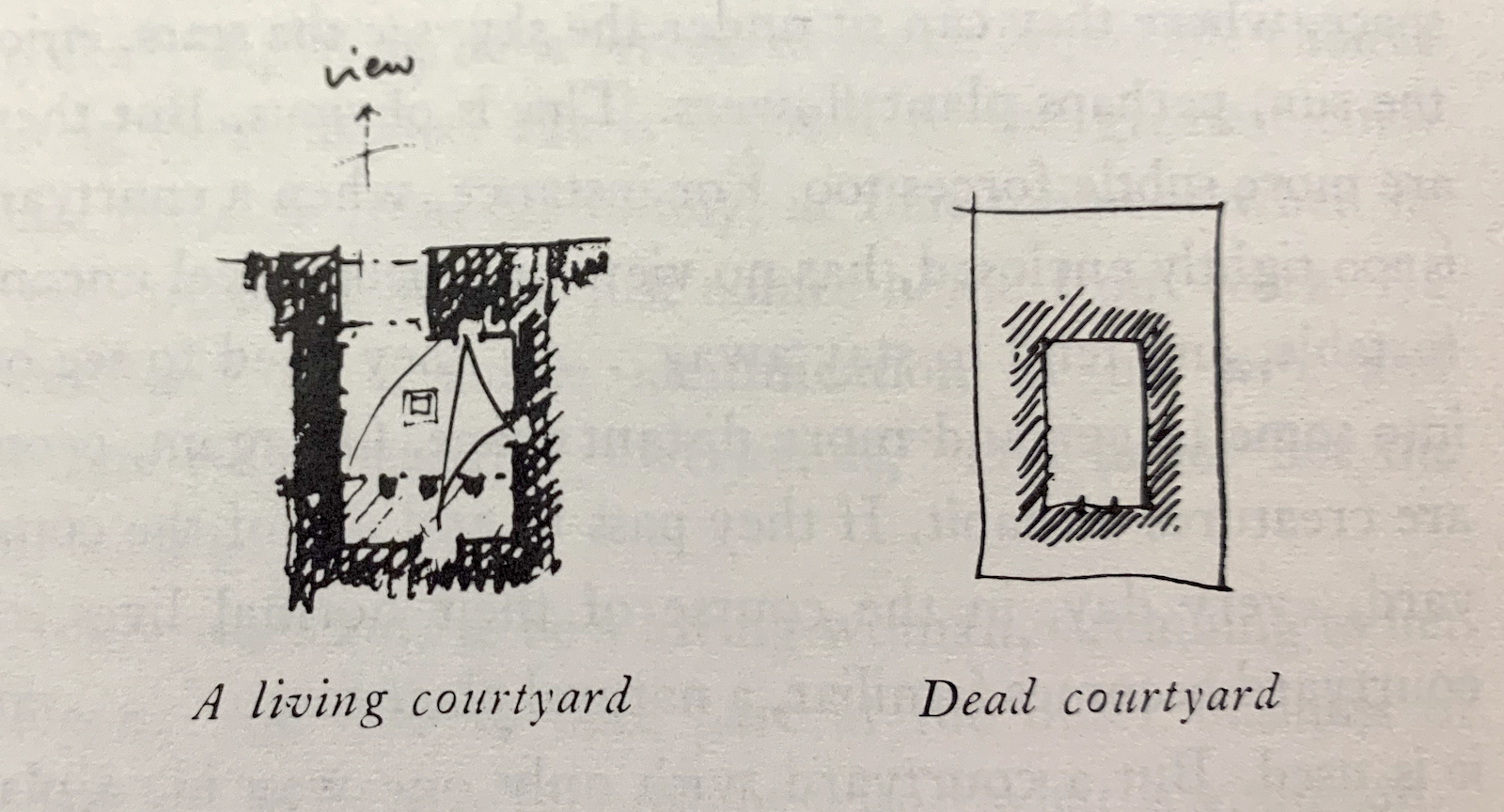

- Dead spaces produce conflicting desires in people. For example, the courtyard on the right makes people want to go outside, but if they enter it produces discomfort and even claustrophobia. Better, in this case, to have no courtyard at all. The living courtyard, on the other hand, is a gradual transition from inside to out, with nooks and corners that give people a choice as to how public or exposed they wish to be.

- Living spaces are self-sustaining; dead spaces are not.

- As a consequence of point 1, dead spaces push conflictedness out into surrounding spaces, and, crucially, into their inhabitants. As Kissane does, I’ll quote Alexander at length due to the importance of this point, that building spaces—whether architectural or digital—for humans to inhabit is an ethical responsibility because it affects how people get to be and feel in the world:

We try to go out, but are frustrated, because the courtyard itself pushes us away. We still need, somehow, to go out; the forces remain within us, but can find no resolution here. We have no way of resolving the situation for ourselves. The unresolved conflict remains underground; it contributes the stress which is building up. First, it reduces our capacity to resolve other conflicts for ourselves, and makes it even more likely that unresolved forces will spill over in another situation. Second, if the force does spill over, it may create even greater tension, in another situation, where there is no proper outlet for it.

Suppose, for example, the people who want to be outside go out instead and sit on the road, where trucks are going by. It is OK. But then perhaps a child gets hurt. Or, even if a child does not actually get hurt, the mother fears for it, and shouts, and conveys a continuous sense of unease to the child, so that his play is spoiled. … In one fashion or another, the effects always ripple out.

You may say—well, people can adapt. But in the process of adapting, they destroy some other part of themselves. We are very adaptive, it is true. But we can also adapt to such an extent that we do ourselves harm. The process of adaptation has its costs. It may be, for example, that the child adapts, by turning to books. The desire to play in the street conforms now to the dangers, and the mother’s cries. But now the person has lost some of the exuberant desire to run about. He has adapted, but he has made his own life less rich, less whole, by being forced to do so.

The “bad” patterns are unable to contain the forces which occur in them.

As a result, these forces spill over into other nearby systems […] the courtyard which fails makes children want to play outside and causes stress and danger in the street.

But these forces make other nearby patterns fail as well. The pattern of the street may not be conceived as a place for children to play. So, suddenly, a pattern of the street, which might be in balance without this force, itself becomes unstable and inadequate. […]

In the end, the whole system must collapse.