frugal hedonism

…essentially advocates for [[Degrowth]] at the personal level: slow down, [[waste]] less, and get off [[the hedonic treadmill]] that's killing…

Waste is what we produce but cannot, or increasingly choose not to use. In a closed ecosystem, waste is inherently unsustainable since it has to go somewhere. When economic processed fail to account for the costs of waste, those costs are externalized to others.

While recycling is often touted as the solution to waste, it has its limitations. Recycling is an industrial process with waste outputs of its own, 17% of what we recycle ends up in landfills anyway, and plastic recycling is essentially impossible with less than 10% of all plastic being recycled, a scam promoted by the oil industry to make people feel better about all the petroleum-based plastic we produce.

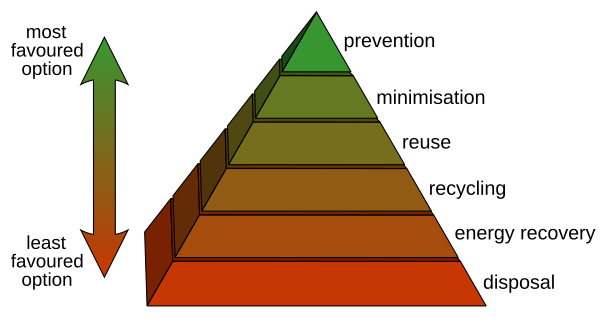

The waste hierarchy is a mental model for minimizing waste that puts recycling as the fourth most-desirable approach. To minimize waste, we should:

From Waste Is an Economic Strategy:

In 1956, Lloyd Stouffer, editor of Modern Packaging Inc., famously (and controversially at the time) declared: “The future of plastics is in the trash can” (Stouffer 1963: 1). Stouffer’s idea addressed an emerging problem for industry. Products tended to be durable, easy to fix, and limited in variation (such as color or style). With this mode of design, markets were quickly saturating (Packard 1960; Cohen 2003). Opportunities for growth, and thus profit, were rapidly diminishing, particularly after America’s Great Depression and the two World Wars, where an ethos of preservation, reuse, and frugality was cultivated. In response, industry intervened on a material level and developed disposability through planned obsolescence, single-use items, cheap materials, throw-away packaging, fashion, and conspicuous consumption…

American industry designed a shift in values that circulated goods through, rather than into, the consumer realm. The truism that humans are inherently wasteful came into being at a particular time and place, by design.

At the time, this ran counter to Americans’ thrifty sensibilities:

Initially, Americans bucked against disposability. Historian Susan Strasser recounts riots by soldiers in train stations in 1917 when the communal tin cup for water was replaced with disposable paper cups (Strasser 1999: 177).

We had to be taught to waste in order to deliver ever-increasing profits to industry, at ever-increasing cost to our environment and future.

…essentially advocates for [[Degrowth]] at the personal level: slow down, [[waste]] less, and get off [[the hedonic treadmill]] that's killing…

…regulation & accept feedback 5. Use & value renewable resources & services 6. Produce no [[waste]] 7. Design from patterns to details 8. Integrate rather than segregate 9. Use…